Read more

Artificial intelligence is making it hard to tell truth from fiction

Experts report that AI is making it increasingly hard to trust what we see, hear or read.......

By

Taylor Swift has scores of newsworthy achievements, from dozens of music awards to several world records. But last January, the mega-star made headlines for something much worse and completely outside her control. She was a target of online abuse.

Someone had used artificial intelligence, or AI, to create fake nude images of Swift. These pictures flooded social media. Her fans quickly responded with calls to #ProtectTaylorSwift. But many people still saw the fake pictures.

That attack is just one example of the broad array of bogus media — including audio and visuals — that non-experts can now make easily with AI. Celebrities aren’t the only victims of such heinous attacks. Last year, for example, male classmates spread fake sexual images of girls at a New Jersey high school.

AI-made pictures, audio clips or videos that masquerade as those of real people are known as deepfakes. This type of content has been used to put words in politicians’ mouths. In January, robocalls sent out a deepfake recording of President Joe Biden’s voice. It asked people not to vote in New Hampshire’s primary election. And a deepfake video of Moldovan President Maia Sandu last December seemed to support a pro-Russian political party leader.

AI has also produced false information about science and health. In late 2023, an Australian group fighting wind energy claimed there was research showing that newly proposed wind turbines could kill 400 whales a year. They pointed to a study seemingly published in Marine Policy. But an editor of that journal said the study didn’t exist. Apparently, someone used AI to mock up a fake article that falsely appeared to come from the journal.

Many people have used AI to lie. But AI can also misinform by accident. One research team posed questions about voting to five AI models. The models wrote answers that were often wrong and misleading, the team shared in a 2023 report for AI Democracy Projects.

Inaccurate information (misinformation) and outright lies (disinformation) have been around for years. But AI is making it easier, faster and cheaper to spread unreliable claims. And although some tools exist to spot or limit AI-generated fakes, experts worry these efforts will become an arms race. AI tools will get better and better, and groups trying to stop fake news will struggle to keep up.

The stakes are high. With a slew of more convincing fake files popping up across the internet, it’s hard to know who and what to trust.

Churning out fakes

Making realistic fake photos, news stories and other content used to need a lot of time and skill. That was especially true for deepfake audio and video clips. But AI has come a long way in just the last year. Now almost anyone can use generative AI to fabricate texts, pictures, audio or video — sometimes within minutes.

A group of healthcare researchers recently showed just how easy this can be. Using tools on OpenAI’s Playground platform, two team members produced 102 blog articles in about an hour. The pieces contained more than 17,000 words of persuasive false information about vaccines and vaping.

“It was surprising to discover how easily we could create disinformation,” says Ashley Hopkins. He’s a clinical epidemiologist — or disease detective — at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. He and his colleagues shared these findings last November in JAMA Internal Medicine.

People don’t need to oversee every bit of AI content creation, either. Websites can churn out false or misleading “news” stories with little or no oversight. Many of these sites tell you little about who’s behind them, says McKenzie Sadeghi. She’s an editor who focuses on AI and foreign influence at NewsGuard in Washington, D.C.

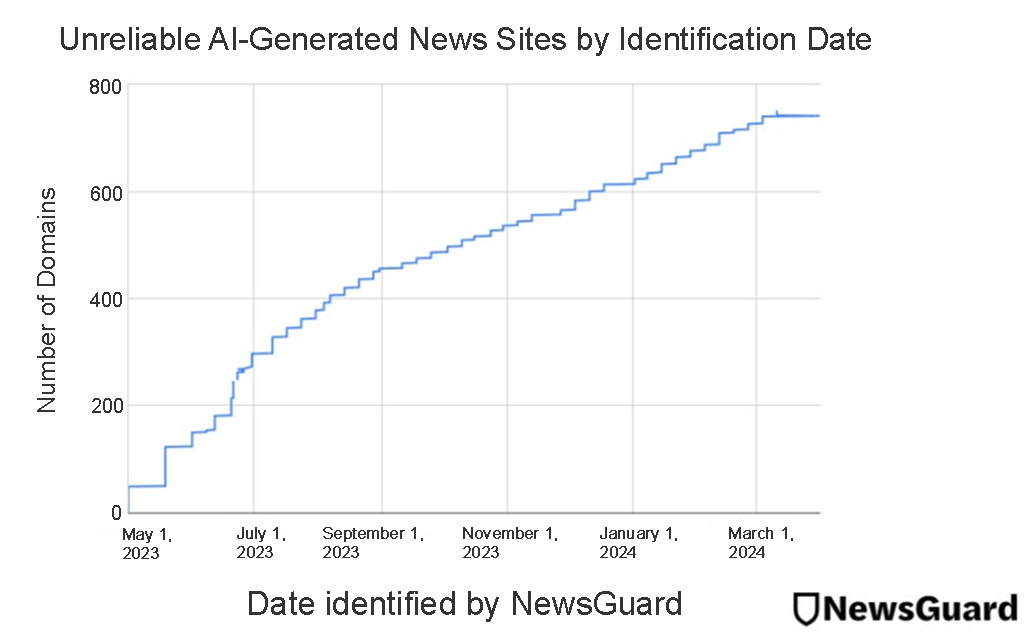

By May 2023, Sadeghi’s group had identified 49 such sites. Less than a year later, that number had skyrocketed to more than 750. Many have news-sounding names, such as Daily Time Update or iBusiness Day. But their “news” may be made-up events.

Generative AI models produce real-looking fakes in different ways. Text-writing models are generally designed to predict which words should follow others, explains Zain Sarwar. He’s a graduate student studying computer science at the University of Chicago in Illinois. AI models learn how to do this using huge amounts of existing text.

During training, the AI tries to predict which words will follow others. Then, it gets feedback on whether the words it picked are right. In this way, the AI learns to follow complex rules about grammar, word choice and more, Sarwar says. Those rules help the model write new material when humans ask for it.

AI models that make images work in a variety of ways. Some use a type of generative adversarial network, or GAN. The network contains two systems: a generator and a detective. The generator’s task is to produce better and better realistic images. The detective then hunts for signs that something is wrong with these fake images.

“These two models are trying to fight each other,” Sarwar says. But at some point, an image from the generator will fool the detective. That believably real image becomes the model’s output.

Another common way to make AI images is with a diffusion model. “It’s a forward and a backward procedure,” Sarwar says. The first part of training takes an image and adds random noise, or interference. Think about fuzzy pixels on old TVs with bad reception, he says. The model then removes layers of random noise over and over. Finally, it gets a clear image close to the original. Training does this process many times with many images. The model can then use what it learned to create new images for users.

What’s real? What’s fake?

AI models have become so good at their jobs that many people won’t recognize that the created content is fake.

AI-made content “is generally better than when humans create it,” says Todd Helmus. He’s a behavioral scientist with RAND Corporation in Washington, D.C. “Plain and simple, it looks real.”

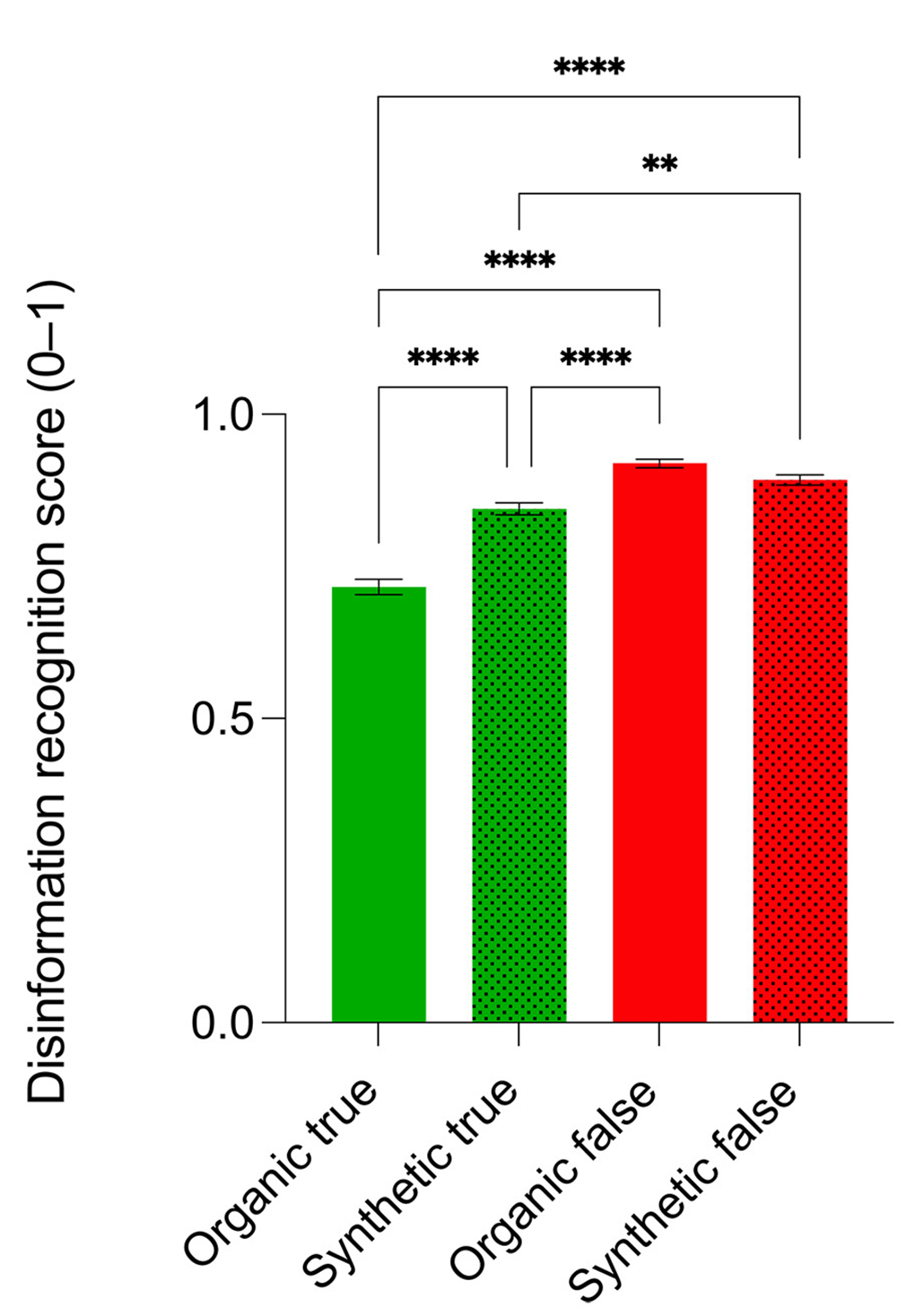

In one study, people tried to judge whether tweets (now X posts) came from an AI model or real humans. People believed more of the AI models’ false posts than false posts written by humans. People also were more likely to believe the AI models’ true posts than true posts that had been written by humans.

Federico Germani and his colleagues shared these results in Science Advances last June. Germani studies disinformation at the University of Zurich in Switzerland. “The AI models we have now are really, really good at mimicking human language,” he says.

What’s more, AI models can now write with emotional language, much as people do. “So they kind of structure the information and the text in a way that is better at manipulating people,” Germani says.

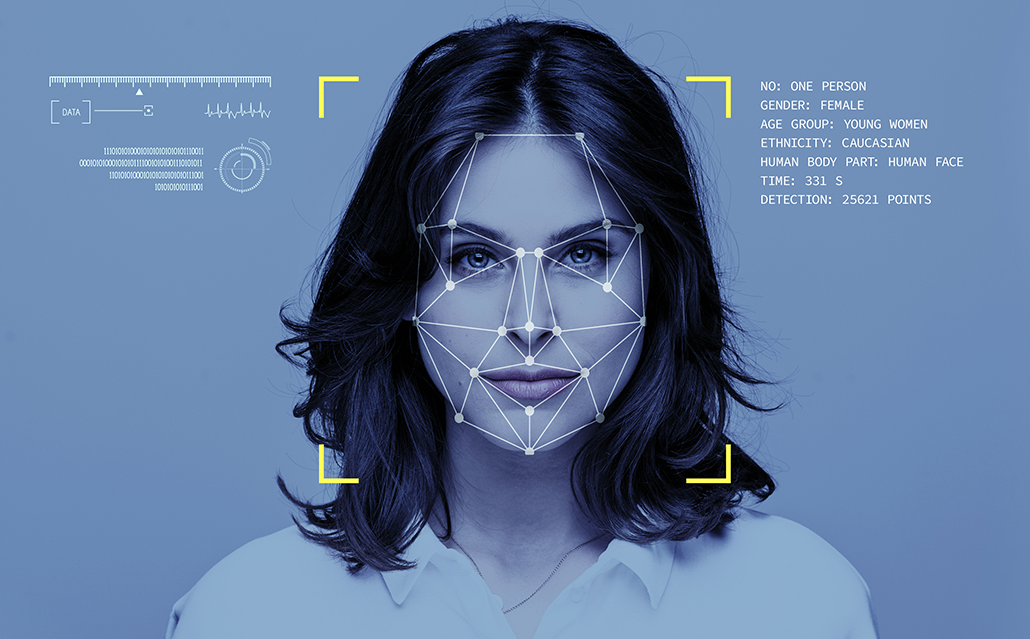

People also have trouble telling fake images from real ones. A 2022 study in Vision Research showed that people could generally tell the difference between pictures of real faces and faces made with a GAN model from early 2019. But participants had trouble spotting realistic fake faces made by more advanced AI about a year later. In fact, people’s later assessments were no better than guesses.

This hints that people “often perceived the realistic artificial faces to be more authentic than the actual real faces,” says Michoel Moshel. Newer models “may be able to generate even more realistic images than the ones we used in our study,” he adds. He’s a graduate student at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia, who worked on the research. He studies brain factors that play a role in thinking and learning.

Moshel’s team observed brain activity as people looked at images for the experiment. That activity differed when people looked at a picture of a real face versus an AI-made face. But the differences weren’t the same for each type of AI model. More research is needed to find out why.

How can we know what’s true anymore?

Photos and videos used to be proof that some event happened. But with AI deepfakes floating around, that’s no longer true.

“I think the younger generation is going to learn not to just trust a photograph,” says Carl Vondrick. He’s a computer scientist at Columbia University in New York City. He spoke at a February 27 program there about the growing flood of AI content.

That lack of trust opens the door for politicians and others to deny something happened — even when non-faked video or audio shows that it had. In late 2023, for example, U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump claimed that political foes had used AI in an ad that made him look feeble. In fact, Forbes reported, the ad appeared to show fumbles that really happened. Trump did not tell the truth.

As deepfakes become more common, experts worry about the liar’s dividend. “That dividend is that no information becomes trustworthy — [so] people don’t trust anything at all,” says Alondra Nelson. She’s a sociologist at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J.

The liar’s dividend makes it hard to hold public officials or others accountable for what they say or do. “Add on top of that a fairly constant sense that everything could be a deception,” Nelson says. That “is a recipe for really eroding the relationship that we need between us as individuals — and as communities and as societies.”

Lack of trust will undercut society’s sense of a shared reality, explains Ruth Mayo. She’s a psychologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel. Her work focuses on how people think and reason in social settings. “When we are in a distrust mindset,” she says, “we simply don’t believe anything — not even the truth.” That can hurt people’s ability to make well-informed decisions about elections, health, foreign affairs and more.

An arms race

Some AI models have been built with guardrails to keep them from creating fake news, photos and videos. Rules built into a model can tell it not to do certain tasks. For example, someone might ask a model to churn out notices that claim to come from a government agency. The model should then tell the user it won’t do that.

In a recent study, Germani and his colleagues found that using polite language could speed up how quickly some models churn out disinformation. Those models learned how to respond to people using human-to-human interactions during training. And people often respond more positively when others are polite. So it’s likely that “the model has simply learned that statistically, it should operate this way,” Germani says. Wrongdoers might use that to manipulate a model to produce disinformation.

Researchers are working on ways to spot AI fakery. So far, though, there’s no surefire fix.

Sarwar was part of a team that tested several AI-detection tools. Each tool generally did a good job at spotting AI-made texts — if those texts were similar to what the tool had seen in training. The tools did not perform as well when researchers showed them texts that had been made with other AI models. The problem is that for any detection tool, “you cannot possibly train it on all possible texts,” Sarwar explains.

One AI-spotting tool did work better than others. Besides the basic steps other programs used, this one analyzed the proper nouns in a text. Proper nouns are words that name specific people, places and things. AI models sometimes mix these words up in their writing, and this helped the tool to better home in on fakes, Sarwar says. His team shared their findings on this at an IEEE conference last year.

But there are ways to get around those protections, said Germani at the University of Zurich.

Digital “watermarks” could also help verify real versus AI-made media. Some businesses already use logos or shading to label their photos or other materials. AI models could similarly insert labels into their outputs. That might be an obvious mark. Or it could be a subtle notation or a pattern in the computer code for text or an image. The label would then be a tip-off that AI had made these files.

In practice, that means there could be many, many watermarks. Some people might find ways to erase them from AI images. Others might find ways to put counterfeit AI watermarks on real content. Or people may ignore watermarks altogether.

In short, “watermarks aren’t foolproof — but labels help,” says Siddarth Srinivasan. He’s a computer scientist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. He reviewed the role of watermarks in a January 2024 report.

Researchers will continue to improve tools to spot AI-produced files. Meanwhile, some people will keep working on ways to help AI evade detection. And AI will get even better at producing realistic material. “It’s an arms race,” says Helmus at RAND.

Laws can impose some limits on producing AI content. Yet there will never be a way to fully control AI, because these systems are always changing, says Nelson at the Institute for Advanced Studies. She thinks it might be better to focus on policies that require AI to do only good and beneficial tasks. So, no lying.

Last October, President Biden issued an executive order on controlling AI. It said that the federal government will use existing laws to combat fraud, bias, discrimination, privacy violations and other harms from AI. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission has already used a 1991 law to ban robocalls with AI-generated voices. And the U.S. Congress, which passes new laws, is considering further action.

What can you do?

Education is one of the best ways to avoid being taken in by AI fakery. People have to know that we can be — and often are — targeted by fakes, Helmus says.

When you see news, images or even audio, try to take it in as if it could be true or false, suggests Mayo at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Then try to evaluate its reliability. She shared that advice in the April issue of Current Opinion in Psychology.

Use caution in where you look for information, too, adds Hopkins at Flinders University. “Always seek medical information from reliable health sources, such as your doctor or pharmacist.” And be careful about online sources — especially social media and AI chatbots, he adds. Check out the authors and their backgrounds. See who runs and funds websites. Always see if you can confirm the “facts” somewhere else.

Nelson hopes that today’s kids and teens will help slow AI’s spread of bogus claims. “My hope,” she says, “is that this generation will be better equipped to look at text and video images and ask the right questions.”

0 Reviews